I was hanging out with other math graduate students last night, having dinner and a beer before going to a

Live Arts presentation featuring experimental computer-generated music.

Socializing with grad students is an eclectic combination of typical small-talk, pseudo-intellectual babble, and pure nerdiness. Amidst the pseudo-intellectual babble, religion is often a topic of interest.

One of my friends said something that I've heard enough times to trigger quite a number of thoughts on it: When faced with the question of whether there is any reason for living our lives, especially in any sort of moral way, it is "natural" to look to (or create) religion for answers.

I don't know what struggles this particular friend has with these questions, but I've noticed that in general this kind of statement is used to explain religion

away. The implication can either be patronizing (as in, "Oh, well, it's fine that you believe that... it's perfectly natural") or condescending (as in, "How can you still believe that in this enlightened age?").

But the obvious question is, what else should one turn to? It sometimes seems like a blasphemous question in the academy, the church of secularism. I wondered aloud what would become of society if most of the world started to believe there really is no transcendent meaning to the world.

As if annoyed, my friends responded that the world has gotten on for a long time already, and it would surely continue on the way it is. This statement is highly presumptuous, and then again it is also rather depressing.

Presumptuous, because to say such a thing is to utterly fail to acknowledge the achievements of religious worldviews. For instance, to act as if the Christian way of thinking had nothing to do with the achievements of the Western world is, I dare say, shockingly stupid, though many people who act this way are not stupid.

Depressing, because it implies that not only is there no meaning, but there really has never been. The things we have accomplished as human beings have only come about because we wanted to do something with our little blips of existence in this meaningless universe. Under this philosophy, we humans would continue to do that even if we didn't believe in God or anything else, because we just can't help it.

In light of how depressing this idea is, I suppose religion is "natural." But I was musing on that word for a while, and I realized that there are really at least two senses in which we use it.

One use of the word "natural" is when we're saying something is easy, or obvious, as in, "It's only natural that he would think only of himself." It's the way we are when we're not trying very hard. Thus my drum line coach in high school used to yell at us, "Don't just do whatever feels natural! Do it right!"

On the other hand, we sometimes use "natural" in a more positive sense to mean that something feels right. When I started doing mathematics as a young child, it felt natural to me. For others, this could've been used in the first sense, meaning it came easily to me. But for me, it was more than that. I worked hard at math because it felt right.

You don't get good at anything just by taking it easy. You have to do more than what comes "naturally" to you. That's the first sense of the word. But surely when you find something you love to work hard at doing, it feels "natural" to you. You feel you are in your element.

In this way, I think at least a few of the world's religion could be considered quite "natural," in the second sense of the word. They make sense. Once you carefully consider their deepest and most powerful teachings, you can see how someone might believe such an idea.

Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism (for example) all have ideas that really make sense of the world. In that sense it is "natural" to turn to one of them for answers to questions about the meaning of life. It makes sense.

Atheism, on the other hand, doesn't seem natural to me at all. It doesn't feel right. Is there really no transcendent meaning? What is the point, then?

But in the first sense, atheism is very natural, in the sense that it really is the most obvious answer. Is there a God? Well, I can't really see one, so I guess not. This is a very "natural" answer.

I imagine atheists would be extremely divided about this statement. I have read many opinions (from atheists) that say much the same thing that I am saying. Atheism is the obvious answer, and it's only this irrational desire for the second kind of "natural" that leads us to develop religion.

But I imagine other atheists would be deeply frustrated with my evaluation of their beliefs. Many atheists have had to really struggle to come to the conclusions about life they now hold. Given the culture in which they live, it is often a battle to leave the faith of one's youth and embrace a life of not knowing if there's really any point to it all.

I certainly don't want to diminish that struggle; I take it seriously. Yet I wonder if atheists take seriously enough the way in which religion has created a way for society to pass on the

virtue of struggling for one's beliefs. "Seek, and ye shall find."

Christianity, in particular, does not assume that it is the default belief. (Many atheists, on the other hand, claim that atheism

is the default belief.) Even where it is culturally dominant, Christianity admits and even insists that it is not the "natural" thing to believe.

This is why Christianity says faith is so important. True, "faith" can become a tool that the powerful use to brainwash the weak; but in its purest form "faith" is simply a statement of belief in something that is not obvious, yet is extremely important if it's true.

What if we lived in a society where struggle for one's beliefs was not considered a virtue? Sure, atheists are typically known for struggling to seek out knowledge

now, in the culture in which we find ourselves, but what if it were different? What if no one felt the slightest urge to believe something that wasn't immediately apparent to all people?

Science would utterly collapse, just as much as any religion. Indeed, science

is a religion, from a certain point of view. Although it easily passes as the true universal, uniting people from all cultures and all faiths, it really isn't any such thing.

Anyone who does math or science goes through a process of initiation, in which knowledge is revealed through many, many stages. Scientific knowledge is not natural in the first sense--it is not obvious--but it is natural in the second sense, in that once you see all the evidence, it begins to feel very natural, even if it's surprising.

To me, the truly atheist worldview has nothing of this second kind of naturalness that both scientific and religious knowledge have. Atheism just doesn't explain why. Worse, it almost seems to discourage asking such questions. All we can really know, it seems, is

what.

Of course, my friends may continue to disbelieve in religion because religion lacks

evidence, but I think that by this they mean only a certain kind of evidence, which does not include those indescribable connections a believer has with God.

For me, knowledge of God must begin with the heart, and all reason must subordinate itself to the connection found there. Surely this connection is not admitted as evidence by everyone, and perhaps with good reason--whose heart are we to believe, after all?

That is why I hesitate to insist upon how much I really know

about God. I will say I know Him, but my mind is very limited in expressing this. Faith is a matter of the heart, and it is not always natural in the first sense. Yet it is natural in the sense of being beautiful, the way it is meant to be.

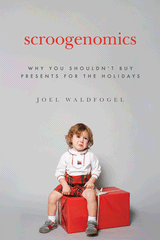

I just a read a classic George Will column on why Christmas spending is so outrageously inefficient. Commenting on the book Scroogenomics: Why You Shouldn't Buy Presents for the Holidays, he points out:

I just a read a classic George Will column on why Christmas spending is so outrageously inefficient. Commenting on the book Scroogenomics: Why You Shouldn't Buy Presents for the Holidays, he points out: