Political, philosophical, and theological reflections from a Christian idealist with libertarian leanings and a professional interest in science and mathematics.

Saturday, October 31, 2009

Happy Reformation Day

This is what everyone celebrates, right?

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Martyrdom of a Mathematician

I finished reading Naming Infinity a while ago, but I never did get a chance to wrap up my blogging on the book. The end really is quite tragic, and all the more so because it's a true story.

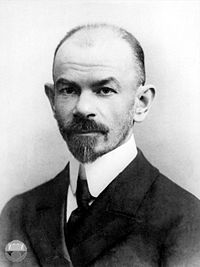

I finished reading Naming Infinity a while ago, but I never did get a chance to wrap up my blogging on the book. The end really is quite tragic, and all the more so because it's a true story.There is so much to say about all that Dmitri Egorov, Nikolai Luzin, and Pavel Florensky did for mathematics and science, and how their faith influenced their work. But since I have to choose what to focus on in a little blog post, I will choose to talk about how they were treated on account of their faith.

Pavel Florensky and Dmitri Egorov both died for their faith. It's a complicated story, and they both went down distinctly different paths, but in the end they both had the same problem--they were openly Christian under a militantly atheist regime.

Pavel Florensky was a Russian Orthodox priest, but he was also a scientist and inventor, and he is part of this story because he was very close friends with both Egorov and Nikolai Luzin, the other member of this "Russian trio."

I suppose it didn't help him that he insisted on wearing his white priest's cassock while delivering his scientific papers. You can kind of guess how the Soviet police eventually got to him--they "proved" that he was the leader of a counter-revolutionary organization, which of course he had never heard of. They shipped him off to a prison camp where he continued scientific research, but I guess they didn't even want him doing science as a prisoner.

In 1937, Florensky was sentenced to be shot. He was executed on December of that year. Recent evidence suggests the details of this death were not pleasant:

According to this information, in December 1937 Florensky was brought from the Solovetsk Islands to Leningrad, where for a while he was in a prison cell in the "Big House," the headquarters of the Leningrad secret police.... Then, according to this new evidence, Florensky was forced to undress, his hands and feet were bound, and he was taken along with several hundred other people in a convoy of trucks to the Rzhevsky Artillery Range, near the town of Toksovo, about 20 miles south of Leningrad. There, we are told, they were all shot.What causes certain regimes to have such an irrational hatred of religion (or any dissenting view) so as to treat someone in this way?

Egorov didn't fare much better. What's crazy is that he simply insisted that his religious views were a private affair, and that all views should be tolerated in the university. Nevertheless, when he was arrested in 1930 the charge included "mixing mathematics and religion." Can you imagine living in a country where that's a crime?

While in prison Egorov prayed daily, including practicing the "Jesus Prayer," despite persecution from the guards. He eventually died there in prison due to digestive failure (which had already been a problem before being sent to prison, where his health only deteriorated). His last words are reported to have been, "Save me, O God, by Thy name!" from Psalm 54--which according to the authors of this book were "appropriate to his Name Worshipping creed."

Nikolai Luzin was not martyred for his faith, but he came pretty close. In the tragic "Luzin affair," he was basically put on trial for his faith--the crime was being tied to anything considered anti-Soviet, including the old monarcy and Christianity. Kind of ironic, considering Luzin at one time had been a sympathizer with the revolutionaries.

It's really depressing to see a lot of those big names of mathematics listed among the people who attacked Luzin, such as Alexandrov, Khinchin, Sobolev, Kolmogorov, Liusternik, and Pontriagin. Most of these are names I've heard at one time or another in my analysis classes.

But that's part of why I write this. Who knows what will ultimately draw us to such evil? It may be that a compelling ideology will grip our hearts so tightly that we lose all sanity. It appears as if a whole country was led into insanity by such an ideology. I don't think any amount of intelligence or wisdom can prevent it. Evil cuts through all of our hearts.

In the end Luzin was spared, thanks to the intervention of a famous physicist of the time, Peter Kapitsa. It's still not entirely clear why Stalin spared Luzin in this instance. He got rid of plenty of other people who were just as valuable as scientists. Perhaps we'll never really know.

What a change it is to think about mathematicians as people who suffered for their beliefs! All you typically hear is about how these child geniuses grew up to prove amazing theorems; but rarely is it ever mentioned that mathematicians have been people who struggled through real trials.

And it puts things into perspective. My friends in grad school were talking about this, and one of us said, "Next time we start to complain about departmental politics, I guess we should keep this in mind." We are so blessed to live in a country where freedom is a given.

But finally, this story really is an inspiration to me, in that it makes me contemplate how to integrate my faith completely with my occupation. It's interesting to read the author's of this book struggle with this idea:

"In concluding that mysticism helped Russian mathematicians in the development of descriptive set theory, we have had to overcome our own natural predispositions. Both of us are secular in our outlooks--far from being Name Worshippers ourselves. We did not start out writing this book in order to come down on the side of religion in the infamous science-religion debates that have occupied so large a place in recent public discussions."As Jesus Christ put it, Wisdom is vindicated by her deeds. There really is no need to endlessly debate over religion and science. The faithful simply ought to pursue knowledge with all their heart, and they will bear fruit.

That's my goal in life--a unified pursuit of knowledge. Incidentally, that's why I've been loving Florensky's Pillar and Ground of the Truth. Maybe I'll start blogging about that soon.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

A Bloody Sacrament

In the midst of all the recent debate on health care, I've realized that conceptually in our culture we have started to lean toward creating a new state religion. This religion has hospitals instead of churches, and doctors instead of priests.

In the midst of all the recent debate on health care, I've realized that conceptually in our culture we have started to lean toward creating a new state religion. This religion has hospitals instead of churches, and doctors instead of priests.The goal is not to inherit eternal life, but simply long, hopefully comfortable life; faithful obedience certainly has its rewards. Instead of a church treasury, we have insurance companies, and all are required to tithe regularly.

Doctors are entrusted with the salvation of our people. This is clear from the fact that no one asks for the price of health care before going to get it. If you thought you were going to the doctor just to receive goods and services, you'd want to know the price ahead of time.

No, it's not goods and services you go to your doctor to receive. You are not a customer. You are a sinner in need of baptism--you need to be made whole again. Your life is incomplete without it.

(I'm convinced this is why natural market mechanisms have failed to keep health care costs low. It is why every transaction between you and your doctor has to go through your insurance company, and for that reason costs are uncontrollable.)

(Ironically, actual religion has become more market-based, as evidenced by those obnoxious church billboards I see advertising such perks as "great worship, great fellowship." For some reason I see these mostly when I'm in Texas.)

Every Sunday I go forward to receive the Lord's supper at my church. It is "an awesome and unbloody sacrifice," a sacrament to make me whole again, to feed me with the life of Christ.

Someone once referred to abortion as a "bloody sacrament" of our culture. I can see why. Who is in greater need of being made whole than a woman who finds herself in the position of carrying in her womb a human being she cannot care for?

What I hadn't thought about was how the priests themselves, the administrators of this bloody sacrament, actually see what they're doing. A remarkable article on LifeSiteNews.com gave me a lot to contemplate.

The article reports on an abortionist who wants to take seriously the moral dilemmas that come with actually performing abortions, yet does not want to conclude that there should be any legal limits on abortion. In the end, both her stance on the issue and her tone become quite religious.

This excerpt caught me as particularly striking:

See with what reverence the abortionist treats the life she is destroying! It is like a priest handling the very body and blood of Our Lord, carefully consecrating it and feeding it to his congregation, who eat gratefully (sometimes ungratefully).To answer the questions, Harris notes that the "violence" of abortion must be acknowledged, and relates a "bizarre" experience she once had of observing a premature baby struggling to survive immediately after dismembering an unborn child the same age:

The last patient I saw one day was 23 weeks pregnant. I performed an uncomplicated D&E procedure. Dutifully, I went through the task of reassembling the fetal parts in the metal tray. It is an odd ritual that abortion providers perform - required as a clinical safety measure to ensure that nothing is left behind in the uterus to cause a complication - but it also permits us in an odd way to pay respect to the fetus (feelings of awe are not uncommon when looking at miniature fingers and fingernails, heart, intestines, kidneys, adrenal glands), even as we simultaneously have complete disregard for it. Then I rushed upstairs to take overnight call on labour and delivery. The first patient that came in was prematurely delivering at 23-24 weeks. As her exact gestational age was in question, the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) team resuscitated the premature newborn and brought it to the NICU. Later, along with the distraught parents, I watched the neonate on the ventilator. I thought to myself how bizarre it was that I could have legally dismembered this fetus-now-newborn if it were inside its mother's uterus - but that the same kind of violence against it now would be illegal, and unspeakable.

Harris then goes on to explain that she rationalizes the bizarreness of the situation by the "location" of the baby, whether it is "inside or outside of the woman's body," and "most importantly, her [the mother's] hopes and wishes for that fetus/baby." However, she says, "this knowledge does not change the reality that there is always violence involved in a second trimester abortion, which becomes acutely apparent at certain moments, like this one. I must add, however, that I consider declining a woman's request for abortion also to be an act of unspeakable violence."

Does the priest ever wonder how he could possibly perform this act on the body of Christ? Jesus had to die on a cross for this. How can such unspeakable violence be justified for the sake of you who want eternal life? Do you sinners actually think your gratitude is enough to justify this?

But the priest knows that nevertheless his flock needs to be made whole again. He cannot withhold the body of Christ, for it is offered even to sinners.

In the same way, the abortionist reveres the aborted fetus--the awesome and bloody sacrifice--as a little Christ, one who has graciously lost his life to make his mother whole.

And this priest of this holy religion continues to preach the good news to all the nation: that enshrined in our Constitution is a bloody sacrament that can never be taken away. Once we were under the law, but now we are under "choice."

The Son of Man goes as it is written of him, but woe to that one by whom the Son of Man is betrayed! It would have been better for that one not to have been born.

It is no small thing that an abortionist would be honest about what abortion is. But on the other hand, should Judas take the credit for the salvation of the world?

Hat tip: Thanks to Sarah and Krissy for this article.

Monday, October 19, 2009

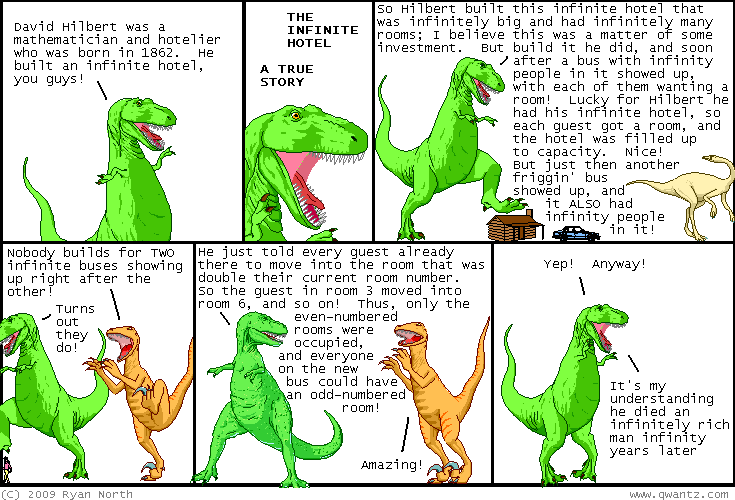

Another math joke

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Orthodoxy

The first letter of PGT, "To the Reader," contains some profound statements of what makes Orthodoxy different from Catholicism and Protestantism. Florensky introduces as a main topic this thing called ecclesiality--which he insists cannot be defined!

Ecclesiality--that is the name of the refuge where the heart's anxiety finds peace, where the pretensions of the rational mind are tamed, where great tranquility descends into our reason. Let it be the case that neither I nor anyone else can define what ecclesiality is!After meditating on this for a little while, he briefly outlines what for him is the fundamental problem with both Catholicism and Protestantism:

Where there is no spiritual life, something external must exist as an assurance of ecclesiality. A specific function, the pope, or a system of functions, a hierarchy--that is the criterion of ecclesiality for Roman Catholics. On the other hand, a specific confessional formula, the creed, or a system of formulas, the text of the Scripture, is the criterion of ecclesiality for Protestants. In the final analysis, in both cases what is decisive is a concept.... But by becoming the supreme criterion, a concept makes all manifestation of life unnecessary.And finally, he offers what he feels to be the strength of Orthodoxy:

The indefinability of Orthodox ecclesiality, I repeat, is the best proof of its vitality.... There is no concept of ecclesiality, but ecclesiality itself is, and for every living member of the Church, the life of the Church is the most definite and tangible thing that he knows. But the life of the Church is assimilated and known only through life--not in the abstract, not in a rational way.... What is ecclesiality? It is a new life, life in the Spirit. What is the criterion of the rightness of this life. Beauty. Yes, there is a special beauty of the spirit, and, ungraspable by logical formulas, it is at the same time the only true path to the definition of what is orthodox and what is not orthodox. [emphasis added]In short, my initial reaction is, "Wow."

...

That is why there is only one way to understand Orthodoxy: through direct Orthodox experience.... [O]ne can become a Catholic or a Protestant without experience life at all--by reading books in one's study. But to become Orthodox, it is necessary to immerse oneself all at once in the very element of Orthodoxy, to being living in an Orthodox way. There is no other way.

It's no wonder so many people in the West are discovering Eastern Christian theology and finding it refreshing. To me, the emphasis on beauty as a genuine measure of orthodoxy is profound, and something in me tells me it's just what I'm looking for.

I wonder where Florensky will take me?

Monday, October 12, 2009

Mystical Mathematicians

The essence of mathematics lies in its freedom.I continue on in my reading of Naming Infinity, that book about religious mysticism and mathematical creativity.Georg Cantor

Chapters 4 and 5 introduce some of the most fascinating mathematicians I've ever read about. Two of them are familiar names from my graduate level Real Analysis class during my first year: Dmitri Egorov and Nikolai Luzin.

Egorov seems more of a distant character than Luzin. He's described as "a very reserved and modest man, so much so that it would be easy to believe that he lived only for mathematics." But if one looks at his actions, one finds a man driven by strong principles and devout religious faith. This becomes a bit more of an issue later, after the Communist take-over in Russia.

Luzin is Egorov's student, a bright, idealistic intellectual who sympathizes with political radicals of his day--at least as a younger man. What really fascinates me is Luzin's story of conversion from atheism to Christianity. It's a story of real crisis, both intellectually and emotionally.

Luzin is Egorov's student, a bright, idealistic intellectual who sympathizes with political radicals of his day--at least as a younger man. What really fascinates me is Luzin's story of conversion from atheism to Christianity. It's a story of real crisis, both intellectually and emotionally."From 1905 to 1908 Luzin underwent a psychological crisis so severe that several times he contemplated suicide. One precipitating event was the unsuccessful revolution of 1905, an event that was sobering for many left-wing members of the intellegentsia.... Luzin was shaken not only by the shedding of blood but also by personally witnessing poverty and suffering.Thankfully, Luzin is deeply acquainted with Pavel Florensky, the third member of this "Russian trio." Florensky studies mathematics with Luzin in Moscow and then later becomes an Orthodox priest. The two of them remain very good friends, and later during the time of Luzin's personal crisis, this friendship becomes extremely important, as the two correspond concerning Luzin's troubled thoughts. Luzin writes to Florensky,

...

Earlier, he had embraced science, materialism, and secularism as the answer to Russia's problems. Now he doubted that these were any answers at all."

"You found me a mere child at the University, knowing nothing. I don't know how it happened, but I cannot be satisfied any more with the analytic functions and Taylor series.... To see the misery of people, to see the torment of life....--this is an unbearable sight....I cannot live by science alone.... I have nothing, no worldview, and no education.Florensky himself is a convert to Christianity, having converted from atheism at the age of 17. Despite having been raised in a secular environment, he believes that one of the sources of Russia's problems is that so many of its brightest minds (like Luzin) are attracted to atheism.

...

"If I do not find a path to seek the truth...I will not go on living."

Florensky therefore provides Luzin with a "path to seek the truth" from his own religious insight. Luzin reads Florensky's thesis "On Religious Truth" (a version of which I happen to have at the moment, thanks to a kind uncle who seems to have every book in the world).

This reading combined with a continued friendship with Florensky leads to a full conversion. In 1908 Luzin writes to Florensky, "I felt as if I had leaned on a pillar...I owe my interest in life to you."

Luzin and Florensky press forward from here into a study of mathematics shaped by a shared interest in Christian mysticism. Florensky becomes an avid supporter of the "Name Worshiping" movement which goes back to chapter 1. Luzin surely knows about this development, even if he never becomes an active participant in the movement.

When it comes to mathematics, Luzin and Egorov are the real experts, it seems, but when it comes to fusing religious, philosophical, scientific, and mathematical thought together, Florensky is the real genius. Some quotes from the book illustrate:

When it comes to mathematics, Luzin and Egorov are the real experts, it seems, but when it comes to fusing religious, philosophical, scientific, and mathematical thought together, Florensky is the real genius. Some quotes from the book illustrate:"Florensky was convinced that intellectually the nineteenth century, just ending, had been a disaster, and he wanted to identify and discredit what he saw as the 'governing principle' of its calamitous effects. He saw that principle in the concept of 'continuity,' the belief that one could not make the transition from one point to another without passing through all the intermediate points.I can't tell you how motivating it is to read about Florensky's religious and mathematical thought, and his influence on Egorov and Luzin. Today's mathematicians often seem inclined to divorce philosophical concerns from mathematics, but that is a sad state of affairs, one from which these early 20th century Russians can liberate us.

...

Florensky faulted his own field, mathematics, for creating this unfortunate monolith. Because of the strength of differential calculus, with its many practical applications, he maintained that mathematicians and philosophers tended to ignore those problems that could not be analyzed in this way--the essentially discontinuous phenomena. Only continuous functions were differentiable, so only those kinds of functions attracted attention... Differentiable functions were 'deterministic,' and emphasis on them led to what Florensky saw as an unhealthy determinism throughout political and philosophical thought in general, most clearly in Marxism.

...

Florensky was convinced that mathematics was a product of the free creativity of human beings and that it had a religious significance. Humans could exercise free will and put mathematics and philosophy in perspective.... Mathematicians could create beings--sets--just by naming them.... The naming of sets was a mathematical act, just as, according to the Name Worshipers, the naming of God was a religious one....

I am also deeply moved by the personal struggles of these mathematicians, and how they had to respond to the crisis of their time. I, with them, am persuaded that the best response to the crises of our time is deeper religious thought, not more secular thought.

As much as I am a fan of interacting with secularism in a healthy and open-minded manner, I think that ultimately secular thought lacks the resources we humans need to move forward. Not that religion doesn't often hold us back; but I think the best cure for stale religion is fresh religious thought. Man, does one ever find that in Florensky.

Still more to come... This book has been really good so far!

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Two can play that game...

But conservatives can play that game, too, it seems. Here's a video from Catholic Vote Action:

I don't know where this one is from, but I might as well throw it in the mix:

A lot of times I wince when conservatives try to outwit liberal satire, but in this case, the liberal video was so bad it made the conservative videos hilarious. Thanks, Alexa.

I'm most disappointed in Will Ferrell's performances. At least when he impersonates Bush, it's funny.

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Christian Capitalism

For those of you who hate Michael Moore, this article I just read probably won't make you like him, but I still recommend reading it with an open mind.

For those of you who hate Michael Moore, this article I just read probably won't make you like him, but I still recommend reading it with an open mind.It's hard to deny that capitalism in our global economy just keeps widening the gap between rich and poor, something that seems antithetical to the life and work of Jesus of Nazareth.

"Blessed are you who are poor, for yours in the kingdom of God.Moore's rambling hardly counts as constructive criticism--what would he replace capitalism with? (I haven't watched his new movie; maybe he argues for some more effective system.) But still, it's hard to simply ignore the simple question: would Jesus approve of capitalism?

...

But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation." (Luke 6:20,24)

I'm going to say the answer is, "No," at least not in the form we have it. Of course Jesus doesn't favor the powerful over the powerless, which is exactly what our current system does.

But then again, what system of economics hasn't done that? What frustrates me to no end is that the alternative liberals come up with to capitalism is big government control of our economy.

Is the irony completely lost on them? Your concern is with shifting power away from the powerful and into the hands of the powerless, and what do you do? You fork all the power over to some big-wigs in Washington. Fail.

The biggest theoretical problem that liberal Christians seem to be unable to overcome is this idea that economics is a zero-sum game. At least that seems to be the idea subtly working behind every sorrowful pronouncement that the rich are getting richer and the poor getting poorer.

I find it sad that Moore's imagination is so limited when he looks at the story of Jesus feeding the 5,000:

"How else did he divide up two loaves of bread and five pieces of fish equally amongst 5,000 people? Either he was the first socialist or his disciples were really bad at packing lunch. Or both."A more imaginative reading of the text might say that Jesus was showing us that we always have more in front of us than we at first realize. Where others see limited resources, we ought to see abundance. Economics is not a zero-sum game.

This to me could be the spirit of a truly Christian capitalism. It would be based on the belief that all human beings are meant to participate in the creative work of God, and from that we pursue ways to overcome the problem of scarcity with innovation.

Probably the biggest difference between Jesus and modern liberals is that, whereas liberals harp on the rich to start caring for the poor, Jesus embraced the poor themselves, and taught them how rich they really were.

Notice how Jesus when speaks to the outcasts of society, he gives them a stringent moral code to live by. This is a message of empowerment. It says to every individual that you can be part of God's work.

That is the message that our society needs. The powerless are actually powerful, not because of some big government program stooping down to rescue them, but because they are inheritors of God's creative energy.

I think if we want a society that follows the words of Jesus, we will stop worrying about what big important people have to say about these big important issues, and start thinking about how each and every individual can be a source of change, a channel though which God's power can enter into this world.

It hardly sounds like economics, but it really is. Entrepreneurship begins with the assumption that human beings have the capacity to produce something valuable. Free trade depends on the notion that by taking what you have in exchange for something I have, I can create something better.

In a truly worthwhile exchange, the net gain in natural resources is always precisely zero, but the net gain in value is always positive. This is because humans, made in the image of God, have the capacity to create, in some sense ex nihilo--just because we cannot create matter does not mean we cannot create something new.

All of this is very abstract, I know, but I just think it would be helpful for Christians to think seriously about the philosophical and theological foundations of our economics. We so easily ally ourselves to secular political and economic philosophies without ever developing our own.

And that's why maybe we should listen to the ramblings of people like Michael Moore every once in a while. For all their faults, they might actually have a point or two.

Saturday, October 3, 2009

Imagining God

A lot of times you hear more or less an accusation that religion invents God for whatever reason--we need something to justify our existence on this planet, we need a crutch to get through tough times, we need a way to control the masses, etc.

So no matter what kind of experience one has had with the divine, perhaps even supernatural encounters with miracles or visions, and no matter what evidence you see for the divine, there will be those who say, well, that's just your imagination.

My response to this would be, I don't think it's just my imagination... but I do think imagination has a lot to do with it.

In the modern world people often try to pick sides between a cold, rational way of looking at things and a romantic view that incorporates mystery and wonder. Often things we say seem like attempts to convert each other from one point of view to the other: "Oh, that's just your imagination," or "Where's your sense of wonder?"

If you pick one side or another, though, you're just cutting yourself in half. Reason and imagination go together, always, and when they don't you're bound to go wrong somewhere.

This is especially clear to a mathematician, actually, since imagination is essential to discovering new mathematics, but reason and logic are the tools by which we tie these new discoveries to old ones.

On a more basic level, imagination and reason are both involved when we ask the question, how do I know this is real? How do I know the world around me is real? How do I know God is real?

How can I really know another person? Oh sure, my capacity to reason plays a role. I have to learn patterns in a person's speech and behavior. Social interaction can be just as much a game as anything else, with rules and logic that a master can figure out and manipulate.

But that's not all there is to really knowing a person. My ability to know a person has everything to do with my ability to imagine her. Imagine what it really means for her to be a person. Imagine her as more than a face in the crowd, an individual with an imagination just like mine. She has stories, hopes, and dreams, and she wants to imagine someone else imagining her.

A lot of philosophy is done with the intention of musing on a thought for a while because it's interesting to think about. I could never do philosophy that way, and I'm not doing that now. To me philosophy begins with pain.

There really is nothing quite like the pain of knowing a person deeply, only to be faced with the reality that it really was just your imagination.

It's tempting for someone who has experienced this to retreat and say, it was my imagination that did this to me. If I simply put on my guard, hide behind the cold shell of logic and reason, then I won't experience this pain anymore.

But only those who lose their life find it. It is only by risking yourself enough to imagine someone who might, after all, not even be there, that you can ever truly love someone.

(Am I speaking metaphorically? Sometimes it's hard to tell. Perhaps metaphor just expresses reality so much better than facts.)

Reason grasps for answers; imagination creates possibilities. They need one another. I would not diminish the importance of anyone's attempt to provide reasons for God's existence; but I emphatically believe that imagination is essential to the spiritual life.

Very often our reason flourishes after a rush of imagination. That's how it always works in mathematics, anyway, and I suspect it works that way in theology. It's no wonder the prophets were always telling people to tear down their idols. Idols limit the imagination; they teach us to think of God as smaller than He really is.

Christian traditions have doctrines that they've built up to direct people toward God. I've noticed that when pastors preach about doctrine, they tend to focus on the weakness of ideas outside their own tradition.

What if, instead, pastors focused on the weaknesses of their own tradition? What if each pastor could act as a prophet for his own congregation, urging them to tear down their own idols, and not self-righteously look down on the idols of others?

Would this not liberate the imagination from the chains of "pure doctrine" that we Christians so quickly wrap around ourselves out of sheer vanity? But we are too afraid of a God who speaks out of a whirlwind, a God who meets our questions with more questions, rather than answers.

There are many Christians these days who say we need more apologists, more people explaining why the Bible is fully reliable, showing that evolution is false and creation is true, proving that Jesus rose from the dead, or giving five reasons why there must be a God.

But my honest answer to anyone who asks me why I believe in God is that faith is as risky as love. My faith looks forward in hope to something I don't even understand, but I try to imagine it every day. I try to imagine a world without evil, and I think, God, that's what I pray for.

Sometimes I catch just a glimpse when I see the sun rise on a clear autumn day, or when I hear a voice that I've been waiting all day to hear, or maybe when I just stop and let myself be alone with my own thoughts. Just a glimpse is all. Isn't that all any of us ever really see of those we love?

I don't suppose that will convince anyone of anything, nor do I even think it should. But it's honest, and maybe the more I think about it the more fruit will come of it. That's the cool thing about reason--eventually it can catch up to imagination, before imagination takes another turn.

Until my reason does catch up, though, this little blog of mine will have to act as a bookmark so I can come back to these thoughts. It's hard to shake the feeling sometimes that there's something just around the corner that I'm not seeing.

Life is like that, though, isn't it?