I've just finished reading chapters 2 and 3 of Naming Infinity, a book about mathematics, religious mysticism, and the problem of infinity.

I've just finished reading chapters 2 and 3 of Naming Infinity, a book about mathematics, religious mysticism, and the problem of infinity.Part of the main thesis of the book is that mathematical advances in the early 20th century were profoundly shaped by cultural and philosophical background. Overall, the book tries to compare the very different approaches of the French and the Russians, contrasting the very rationalist with the very mystical.

Chapter 2, however, starts with the Germans. In a way, I suppose the German mathematicians in this chapter (and the next) come across as in between France and Russia, both in geography and in philosophical approach. The

whole mess about set theory starts with the work of Georg Cantor, who proves that there are multiple types of infinity.

whole mess about set theory starts with the work of Georg Cantor, who proves that there are multiple types of infinity.Entering into Chapter 3, we read that Cantor eventually suffers from mental illness in connection with his studies of infinity. He keeps trying to prove something called the continuum hypothesis, which, as it turns out, is not really provable within the axioms of set theory. Poor guy is chasing a phantom.

People respond to Cantor's set theory with mixed reactions. One German that is willing to go to bat for him is David Hilbert, who is busy trying to advance an axiomatic approach to mathematics. Also he has a terrific hat in the picture I found on Wikipedia.

This axiomatic approach is culturally much different from the French approach, which stresses the need for a connection between physical reality and mathematics. In 1900 Hilbert proposes that the continuum hypothesis is one of the most important problems in mathematics--a pure mathematical problem, needing no grounding in physics or other sciences.

It is in this mathematical climate that we meet the three star French mathematicians of the book: Emile Borel, Rene Baire, and Henri Lebesgue. All three are very different people, except they do seem to share in common that they were not born into privilege--their mathematical talents caused them to rise to prominence in France.

The French have a cultural commitment to rationalism, inherited from Descartes, as well as positivism, a product of late 19th century philosophy. Under this philosophy, "once science liberates itself from all metaphysical influences and enters the 'positive stage,' its goal is no longer a metaphysical quest for truth or a rational theory purporting to represent reality. Instead, science is composed of laws (correlations of observable facts) that can be used by the scientists without regard to the nature of reality."

Contrast this with Cantor, whose struggles with infinity are deeply metaphysical and even religious. This is a foretaste of how the Russians will deal with the issues of set theory. But in the meantime, this "French trio" sets out with their own brilliance, eventually hitting a wall of mystery and frustration.

Despite the fact that Borel, Baire, and Lebesgue all make deep discoveries that move the study of infinity forward, eventually they all reject some basic notions of infinite set theory.

Despite the fact that Borel, Baire, and Lebesgue all make deep discoveries that move the study of infinity forward, eventually they all reject some basic notions of infinite set theory.Ernst Zermelo (another mischievous German) comes up with this notion of the "axiom of choice," which all three of the French trio reject.

Kind of bizarre for me to read, really, because the very first day of Real Analysis in grad school was using the axiom of choice to generate a set that isn't Lebesgue measurable. History is full of irony.

In any case, Borel goes all hard-core and starts saying that the only entities that really exist in mathematics are those that can be constructed in finite steps. He abandons his older pursuits and focuses on more "useful" mathematics. Lebesgue can't quite divorce himself from the study of the continuum, but he's rather stuck without certain philosophical tools.

Baire becomes another victim of mental illness in this story of infinity. His already unstable mind isn't helped by the fact that he can't seem to find any way forward through the "intellectual abyss" created by the problem of the infinite.

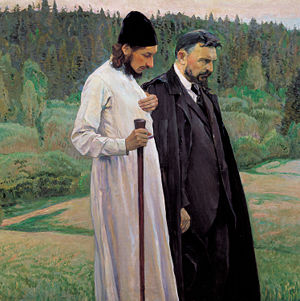

Meanwhile, lurking around the corner seems to be a glimmer of progress in these Name-Worshiping Russian mathematicians who are about to be introduced in Chapter 4. Their secret seems to lie in being open to precisely what the French are closed off to: allowing metaphysics to mix with mathematics.

This has been a good read so far. It's keeping me awake at night, to be sure. It also makes me hope I don't go crazy. Why is there such a strong connection between mathematics and insanity, anyway?

One thing I'm seeing in these first few chapters is that perhaps there really is a need in all of us to embrace mystery, and accept what we cannot understand. Maybe it really can drive a mind insane to try to iron out all the details of a rational system that may simply have boundaries that we can never see.

Mathematics and mystery... at first they don't seem to go hand in hand, but the more I think about it, the more I think they do.

Anyway, I'm excited to continue on through this book!