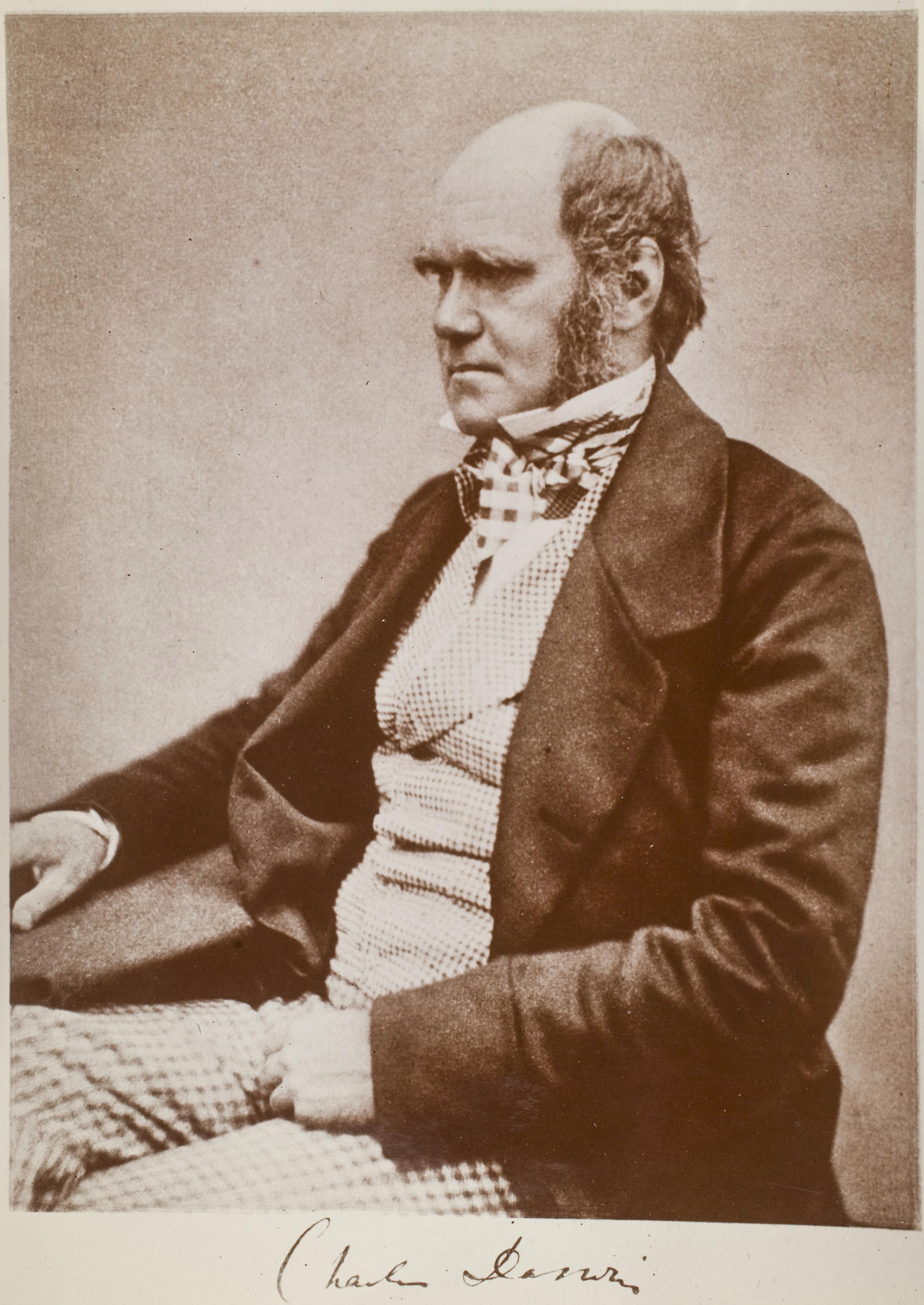

So I found an interesting new book in the New York Times "First Chapters" section, called Darwin's Sacred Cause. The basic thesis of the book is that Darwin's theory of evolution developed out of a complex process of very human thoughts about life, as opposed to simply sitting down to watch Finches one day and deciding animals evolved.

So I found an interesting new book in the New York Times "First Chapters" section, called Darwin's Sacred Cause. The basic thesis of the book is that Darwin's theory of evolution developed out of a complex process of very human thoughts about life, as opposed to simply sitting down to watch Finches one day and deciding animals evolved.In particular, Darwin was a staunch abolitionist, which made the fact of common ancestry of all humans very important to him. Whereas his religious allies in the abolition movement used Adam, he used apes (to boil it down cartoonishly) establishing a common humanity between blacks and whites.

What this shows is that the notion of "purely objective science" is not very useful in the real world. There simply are no observers with no personal attachments to some kind of worldview. A completely detached, impartial judge of reality is a modernist myth, a hero that never existed.

Yet what we have, I believe, is something better. Scientists are and should be like Darwin--real human beings with real concerns about life other than purely mechanistic explanations of how things work. These explanations are key parts of how we see the world, but they are not the whole picture.

Incidentally, I also recently watched an episode of the Colbert Report featuring guest Jonah Lehrer, author of the new book How We Decide. The thesis of this book is that there are two parts of the brain involved in decision-making, which Lehrer calls the "rational" and the "emotional" parts. Good decision-making involves using both in healthy proportions.

Let me quibble with the terminology here. I always think rational means "most in line with truth." Here it's not really being used that way, because, as Lehrer admits, those who think only using this part of the brain have incredible problems in the real world, such as being unable to make simple choices at a grocery store.

Let me quibble with the terminology here. I always think rational means "most in line with truth." Here it's not really being used that way, because, as Lehrer admits, those who think only using this part of the brain have incredible problems in the real world, such as being unable to make simple choices at a grocery store.Indeed, his whole point is that to act in line with the truth, which I would call rationally, means to successfully combine the "emotional" or gut instincts with the more cognative, analytical side of thinking.

Even as a mathematician, I don't think it's possible to leave one side of your thinking at the door. Mathematics has everything to do with intuition, with mental "exploration" being the first real step in solving a problem. Hadamard would agree.

The prevailing modernist conception of objectivity needs to be a ltered. First, we can't step back from reality as observers and pretend we have no attachments to it. Second, we really wouldn't want to. Third, a very real possibility for objectivity still remains after giving up this version.

ltered. First, we can't step back from reality as observers and pretend we have no attachments to it. Second, we really wouldn't want to. Third, a very real possibility for objectivity still remains after giving up this version.

ltered. First, we can't step back from reality as observers and pretend we have no attachments to it. Second, we really wouldn't want to. Third, a very real possibility for objectivity still remains after giving up this version.

ltered. First, we can't step back from reality as observers and pretend we have no attachments to it. Second, we really wouldn't want to. Third, a very real possibility for objectivity still remains after giving up this version.Before explaining what the alternative is, let me point out where I think we go wrong in trying to define objectivity. We tend to think fair = impartial = detached. A fair judge is an impartial judge, which is a judge with no attachments to either party in a given case. That's the common sense of many centuries of tradition.

But we have to avoid thinking impartiality means zero attachment. In order to judge justly, a judge must care very deeply about something we all have in common, namely, our common value as human beings. A judge who doesn't think humans are worth anything has absolutely no reason to judge fairly, nor unfairly.

Thus a judge really ought to have a real attachment to both sides in a case. He ought to care equally for both sides, to see they get a fair trial. The goal is not detachment, but rather broader attachment.

I just think of all the debates in politics about issues like, say, poverty. We tend to imagine there are some who operate on emotion, saying, well, we just have to do something about it, and there are others who operate on cold hard reason, which tells them, no, we have to think about the costs.

I would argue that those who consider the costs are not emotionless (maybe in some cases they are, in which case they should not be trusted). Rather, those who consider the costs are mindful of all people equally--yes, they care for the poor, but they are equally concerned for others whose resources they would have to borrow/take in order to help the poor.

To show genuine concern for all people is to be truly rational when it comes to justice. And I would take that principle and apply it else where.

where.

where.

where.When we talk about objective science, we should not mean science done by robotic people with no attachments. Rather, we should mean people who are willing to stretch their attachments based on the principle that the understanding of physical reality is important.

Much as people would like to make scientific discovery entirely about finding the means to be more efficient with tasks we already want to do, most science is simply not about that. Technological applications are wonderful, but they are often propelled forward by discoveries that initially have no preconceived application. Science is done for the love of understanding.

I think love really is at the heart of everything, especially knowledge. We can't know something without loving it (conversely, we can't really love something unless we know it).

Where do we find any reason to love the physical world? Isn't it just full of mostly lifeless matter, most of which is useless to us and much of which is dangerous? A cynical pragmatist might say we study science simply to master such dangers, so we don't have to be afraid of the physical world.

But I think that we can find meaning in the physical world. Operating under the principle of divine creation, we see that there is more than just stuff to be described; there are meaningful things to be understood. In God science finds its integration point with other concerns of human existence, namely purpose, wisdom, and virtue.

If science can be done objectively, why not religion? I believe love will indeed take us to knowledge, not just of things but of the thing, the person, the God in whom all things hold together. The same objectivity principle applies--we must simply be committed to knowing the universal, rather than our own personal god.

It is only natural that love is a basis for understanding if a personal, knowable God is at the heart of all reality.

So why is any of this relevant? In our culture, being perceived as more objective than the next guy gives you more power. It makes sense that everyone, not only the scientific community but also in the media and in politics, would be scrambling for the title of "most objective."

All I'm saying is, here's a simple test of objectivity. Does this person love all people involved in a discussion? Is he willing to empathize with, and thus truly understand, each point of view? Is he willing to carefully and humbly offer up his own point of view as a possible corrective to faulty points of view?

Maybe this can shed light on some very heated discussions that take place in our culture. For love's sake, I hope it can.

I like the word "quibble"

ReplyDeleteHere is the problem with your view of rationality: you seem to think rationality and concern for the life of a human being are completely independent. Wouldn't a real rationalist, someone who is actually objective, put some value on a human life? You're misunderstanding rationality if you'd say that a rationalist would kill an innocent cat for $5 because "$5 is more than nothing".

ReplyDelete"Rather, those who consider the costs are mindful of all people equally--yes, they care for the poor, but they are equally concerned for others whose resources they would have to borrow/take in order to help the poor."

It's not being mindful of all people equally if the poor person starves to death without the money and the rich person can only go to Starbucks three times per week instead of five.

"Here is the problem with your view of rationality: you seem to think rationality and concern for the life of a human being are completely independent."

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure where you get this. I think I was arguing for quite the opposite idea.

"It's not being mindful of all people equally if the poor person starves to death without the money and the rich person can only go to Starbucks three times per week instead of five."

Ah, I agree with that statement, but I sense in it a preconception of how arguments about poverty are aligned morally. Many people do assume that any opposition whatever solution they've proposed is immoral. But I think we have to be careful.

The question is usually not whether a person should go ahead and starve so that I can spend less money on Starbucks. The question is usually, will this solution to poverty actually leave things worse than they already are?

It's never as simple as it first appears.