The essence of mathematics lies in its freedom.I continue on in my reading of Naming Infinity, that book about religious mysticism and mathematical creativity.Georg Cantor

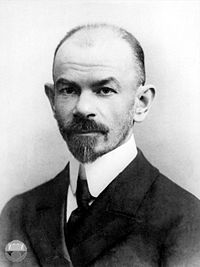

Chapters 4 and 5 introduce some of the most fascinating mathematicians I've ever read about. Two of them are familiar names from my graduate level Real Analysis class during my first year: Dmitri Egorov and Nikolai Luzin.

Egorov seems more of a distant character than Luzin. He's described as "a very reserved and modest man, so much so that it would be easy to believe that he lived only for mathematics." But if one looks at his actions, one finds a man driven by strong principles and devout religious faith. This becomes a bit more of an issue later, after the Communist take-over in Russia.

Luzin is Egorov's student, a bright, idealistic intellectual who sympathizes with political radicals of his day--at least as a younger man. What really fascinates me is Luzin's story of conversion from atheism to Christianity. It's a story of real crisis, both intellectually and emotionally.

Luzin is Egorov's student, a bright, idealistic intellectual who sympathizes with political radicals of his day--at least as a younger man. What really fascinates me is Luzin's story of conversion from atheism to Christianity. It's a story of real crisis, both intellectually and emotionally."From 1905 to 1908 Luzin underwent a psychological crisis so severe that several times he contemplated suicide. One precipitating event was the unsuccessful revolution of 1905, an event that was sobering for many left-wing members of the intellegentsia.... Luzin was shaken not only by the shedding of blood but also by personally witnessing poverty and suffering.Thankfully, Luzin is deeply acquainted with Pavel Florensky, the third member of this "Russian trio." Florensky studies mathematics with Luzin in Moscow and then later becomes an Orthodox priest. The two of them remain very good friends, and later during the time of Luzin's personal crisis, this friendship becomes extremely important, as the two correspond concerning Luzin's troubled thoughts. Luzin writes to Florensky,

...

Earlier, he had embraced science, materialism, and secularism as the answer to Russia's problems. Now he doubted that these were any answers at all."

"You found me a mere child at the University, knowing nothing. I don't know how it happened, but I cannot be satisfied any more with the analytic functions and Taylor series.... To see the misery of people, to see the torment of life....--this is an unbearable sight....I cannot live by science alone.... I have nothing, no worldview, and no education.Florensky himself is a convert to Christianity, having converted from atheism at the age of 17. Despite having been raised in a secular environment, he believes that one of the sources of Russia's problems is that so many of its brightest minds (like Luzin) are attracted to atheism.

...

"If I do not find a path to seek the truth...I will not go on living."

Florensky therefore provides Luzin with a "path to seek the truth" from his own religious insight. Luzin reads Florensky's thesis "On Religious Truth" (a version of which I happen to have at the moment, thanks to a kind uncle who seems to have every book in the world).

This reading combined with a continued friendship with Florensky leads to a full conversion. In 1908 Luzin writes to Florensky, "I felt as if I had leaned on a pillar...I owe my interest in life to you."

Luzin and Florensky press forward from here into a study of mathematics shaped by a shared interest in Christian mysticism. Florensky becomes an avid supporter of the "Name Worshiping" movement which goes back to chapter 1. Luzin surely knows about this development, even if he never becomes an active participant in the movement.

When it comes to mathematics, Luzin and Egorov are the real experts, it seems, but when it comes to fusing religious, philosophical, scientific, and mathematical thought together, Florensky is the real genius. Some quotes from the book illustrate:

When it comes to mathematics, Luzin and Egorov are the real experts, it seems, but when it comes to fusing religious, philosophical, scientific, and mathematical thought together, Florensky is the real genius. Some quotes from the book illustrate:"Florensky was convinced that intellectually the nineteenth century, just ending, had been a disaster, and he wanted to identify and discredit what he saw as the 'governing principle' of its calamitous effects. He saw that principle in the concept of 'continuity,' the belief that one could not make the transition from one point to another without passing through all the intermediate points.I can't tell you how motivating it is to read about Florensky's religious and mathematical thought, and his influence on Egorov and Luzin. Today's mathematicians often seem inclined to divorce philosophical concerns from mathematics, but that is a sad state of affairs, one from which these early 20th century Russians can liberate us.

...

Florensky faulted his own field, mathematics, for creating this unfortunate monolith. Because of the strength of differential calculus, with its many practical applications, he maintained that mathematicians and philosophers tended to ignore those problems that could not be analyzed in this way--the essentially discontinuous phenomena. Only continuous functions were differentiable, so only those kinds of functions attracted attention... Differentiable functions were 'deterministic,' and emphasis on them led to what Florensky saw as an unhealthy determinism throughout political and philosophical thought in general, most clearly in Marxism.

...

Florensky was convinced that mathematics was a product of the free creativity of human beings and that it had a religious significance. Humans could exercise free will and put mathematics and philosophy in perspective.... Mathematicians could create beings--sets--just by naming them.... The naming of sets was a mathematical act, just as, according to the Name Worshipers, the naming of God was a religious one....

I am also deeply moved by the personal struggles of these mathematicians, and how they had to respond to the crisis of their time. I, with them, am persuaded that the best response to the crises of our time is deeper religious thought, not more secular thought.

As much as I am a fan of interacting with secularism in a healthy and open-minded manner, I think that ultimately secular thought lacks the resources we humans need to move forward. Not that religion doesn't often hold us back; but I think the best cure for stale religion is fresh religious thought. Man, does one ever find that in Florensky.

Still more to come... This book has been really good so far!

No comments:

Post a Comment

I love to hear feedback!